The Word "Special" Doesn't Cut It

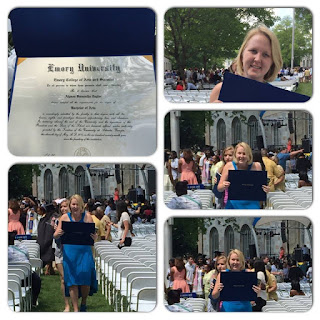

Graduation day at Emory University and my graduation cap referenced a childhood story that my mom would tell me every night when I was a kid, "Once upon a time, there was a beautiful little girl named Alyson Samantha Taylor..." The story would lead into a life lesson I learned that day, usually in reference to being smart, kind, or understanding.

Graduation day at Emory University and my graduation cap referenced a childhood story that my mom would tell me every night when I was a kid, "Once upon a time, there was a beautiful little girl named Alyson Samantha Taylor..." The story would lead into a life lesson I learned that day, usually in reference to being smart, kind, or understanding.Stories such as these reminded me that I was a special child. I was a special person and I could do great things if I worked hard and was kind. Special in this case referring to something positive; alluding to the beauty of my uniqueness and the fact that there's no other Alyson Samantha Taylor like me in the universe.

There's a beauty in being and FEELING special, until of course the connotation of "special" changes.

When I hear the word "special," I'm torn. I quickly recall the Alyson Samantha Taylor stories, but I just as quickly recall being classified as "Special Needs." No matter how much I work or try to be kind, nothing can eliminate the insecurity of being "special needs."

Merriam Webster defines special needs as the following: "any of various difficulties (such as physical, emotional, behavioral, or learning disability or impairment) that causes an individual to require additional or specialized services or accommodations (such as in education or recreation)."

Sounds simple enough, right? Learning or behavior difficulties, you are placed into a "special" learning environment.

However, this black-and-white definition of special education programs fails to address the social implications involved. Frankly, if I may be so bold, adults fail to recognize the emotional impact of what exactly calling a child "special needs" does.

I was considered a special-needs student in Pre-School and Kindergarten, then a quasi-special needs student in Elementary School as I transitioned out. Developmental Apraxia mixed in with my poor motor functions with physical activity and of course mathematics (which was and still is a foreign language to me) - I was delayed.

Did I know I was delayed? No, not at all.

Did the school know? Yes they did, hence they put me in special ed.

Granted this was many years ago, some of it is hazy. However, I can still recall the feeling of inferiority. My parents didn't need to tell me I was "special needs." I knew it by the way my classmates and I were treated. There was a reason why there was a short yellow bus, there was a reason why we had our own playground and designated playtime, and why the huge mass of 'normal' kids were dropped off at one side of the school and our small group was dropped off at the other.

I recall math assignments, while learning addition. Some kids could count on their fingers, but my brain couldn't grasp how this written number equated to how many fingers I had. So I used visuals and would imagine each written number had dots on it:

I would see other "normal" kids assignments and they didn't have dots. They could do it all in their heads, which apparently is "normal." I forever questioned how they could even do addition without dots on their page, they must be smarter than me if they don't count dots, right?

Today, when I add a tip at the bottom of the receipt, I still count these dots. And, guess what, I see others counting on their fingers and some even talking to themselves to calculate the total. Yet, even though we can all get to the same answer in different ways as adults-as children there is only one "normal" way and other methods that are "special."

In the earliest days of school and educational paths, children quickly understand this unspoken totem pole of intellect. You have your "special" kids for those that struggle and need to draw dots on their math assignments, then the "normal" kids that are just squeezed in the middle with no dots on their math homework, and then the "honors" kids which are the brightest, most intelligent kids who can do everything in their head.

I can say I've spent time at each stage of this totem pole. Please note, this reference to a totem pole is meant to see how students, at least kids, see their counterparts. This may be more education related, but there are issues that arise in each academic setting.

When you're in special-education, people have lower expectations for your behavior and sometimes intellectual capacity. You aren't expected to be as smart as the "normal" or "honors" kids, so the standards are drastically lowered and even the smallest of feats are the greatest successes. This is acceptable in some circumstances, but it can also be dangerous if the student themselves starts to set lower standards for themselves.

Then the "normal" classes, I'd say is actually the worst of the three. When you're "normal," you do not have the strong support system as once given in special-education so you get less help. You also fall victim to having the mediocre teachers that aren't qualified in a special-education setting nor are they quite prepared for an "Honors" classroom either. You are basically stuck in this limbo of mediocrity and averageness unless you can find a way out-either climb up the pole or climb down the pole.

The "honors" classes, do they have their issues too. Here you can have AMAZING teachers; they are bright and they challenge you. But, sometimes they expect a lot more out of you and can provide way less support. Here they have the idea that, "Oh, you're a bright student, you can figure it out on your own" which ingrains a mentality that you don't need to ask for help.

See, each level of this totem pole has its pros and its cons. I know that now after years in school, but more importantly I know just how complex it is to say your child is "special needs."

See when adults and educators talk about it, they talk about it as an education program. Which is fine, they would see that especially if they themselves haven't been in a special needs program. However, when a child hears they are "special needs" and then witnesses the other "normal" or "honors" kids-they see themselves as abnormal and negatively different from the others.

Recall, kids like to "fit in." Being special-needs disrupts this; popular and smart kids are not "special needs" on the playground, at least in the child's eyes.

I struggle with the word "special." Honestly, I despise a word that can be utilized so positively to describe the unique beauty of a child and then simultaneously be negatively utilized to describe their differences and delays. A word should not be THIS complicated.

Likewise, the only difference I see between the special-needs, the normal, and the honors kids are how they are ultimately treated by the others around them-their educators, their parents, supervising adults. If we are all honest, when was the last time you saw a teacher or an adult treat a special-needs child the same way they would as a "normal" child. It's sadly pretty rare, right? It shouldn't be rare. Just because one is special-needs does not make them stupid, dumb, nor qualifies treating them with any less respect as you would a "normal" child.

Frankly kids should not need to be confused as to whether or not this word "special" is a good or bad adjective. So perhaps next time you matter of factually say your child is 'special needs,' I can honestly tell you that your child will not want to be

special anymore.